If You Want People To Remember Your Video Ads, Remember The Colonoscopy Experiment

In 2020 there are more ways than ever to distribute and create video content and brands continue to take advantage of the evolving medium to enhance their storytelling capabilities and build an audience.

However, there is an issue here. Advertisers are spending a lot of time and money on creating high-quality video content for an audience who are more likely to forget ever watching that content than they are to correctly recall the specific brand on display.

So, how exactly do you create a memorable video without including a gorilla playing Phil Collins on the drums? New research from Unruly suggests that advertisers can better equip their ads for memory by leveraging a mental short-cut known as the peak-end rule.

Coined by the Nobel Prize winning behavioural psychologist Daniel Kahneman, the theory behind the peak-end rule is that we judge experiences, whether they’re positive or negative, based on how we felt at it’s peak and at its end instead of judging the experience as a whole. This idea that our brain uses feelings to construct memories was proven most famously in Kahneman’s experiment from 1996 which involved colonoscopy patients. If you do not already know what a colonoscopy is, don’t google it.

The patients were randomly divided into two groups. The first group underwent a painful procedure for a standard amount of time, whilst the second group experienced a longer procedure where the final few minutes were less painful then the rest. Bizarrely the study found that those who experienced the longer procedure rated it as less unpleasant than the group who experienced the shorter procedure. This contributed to a more positive overall impression of the experience and increased the chance of a second visit to the same physician for future procedures.

In this experiment Kahneman discovered that we remember moments differently according to the level of emotional intensity felt at the time and this memory bias can change how we behave. Whilst colonoscopies seem a far cry from John Lewis Christmas adverts, the notion of memory bias is something that all advertisers should be aware of, especially when anywhere between 75% – 84% of advertising cannot be correctly recognised or recalled. But can advertisers really increase the effectiveness of their video content by implementing the teachings of the peak-end rule? New research from Unruly and Richard Shotton suggests so.

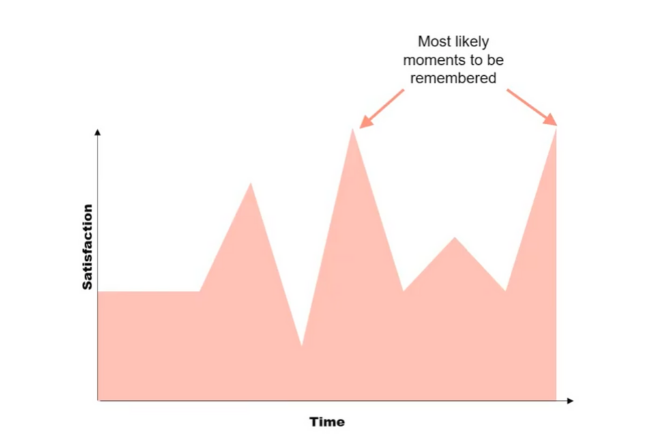

By working with Affectiva, a facial recognition company, Unruly was able to track the emotions felt by respondents as they watched videos based on changes to their facial expressions in real-time. The videos were then categorised according to three specific groups defined by Richard: videos without emotional peaks, videos with multiple peaks throughout and videos where the highest peak occurs at the end.

The results followed the peak-end rule hypothesis almost exactly as the memory of each viewing experience was significantly correlated with the level of emotional response recorded. When the respondents were re-contacted within a week of exposure and shown a series of frames from each advert, the level of recognition was significantly higher for the videos which featured an emotional peak either in the middle or at the end based on a 99% confidence interval.

Going beyond recognition, the same respondents were also asked which brand each video was for and again recall was significantly higher in the adverts which produced moments of emotional intensity. Further analysis showed that the success of the ads was not just down to the sheer amount of emotion produced, but whether the brand was present during those peak moments. Unruly’s research demonstrated that by producing at least one peak moment of emotional intensity during which the brand was present the chances of correct brand recall improved by over 100% (10% vs 21%).

As with Kahneman’s experiment the duration of the experience was also a factor. The ads with multiple peaks were between 1 – 2 minutes in length whilst the ads where the peak came at the end clocked in at a traditional 30 seconds and yet the strong response across both sets of ads shows that regardless of the duration, as long as the experience features a peak moment of emotion, the chance of it being remembered positively improves.

This just goes to show that shorter ads can be just as effective as longer ads at building memory structures based on the location of the emotional peak. Richard Shotton, founder of Astroten a behavioural science consultancy commented: “This new series of experiments shows that the implications of the peak-end rule stretch far beyond medicine. If marketers want to create the most memorable customer experiences or ads then these findings are relevant.”

It must be said that the ads which did not produce a peak moment were not bad ads. In fact, without testing you would even argue that they were quite good ads based on the production quality, the soundtracks, and the amount of visible branding etc.

The truth is that there are very few “bad” ads in the derogatory sense of the word (and even those few truly awful ads can ingrain themselves into memory based on negative emotions such as disgust, looking at you, Peloton), but as video ad spend increases it makes it harder and harder to cut through the noise. Brands can improve their chance of creating something memorable by shaping their video content to produce moments of intense emotion that exploits the memory bias that all humans are guilty of.

To find out more about the peak end rule watch Alex’s virtual presentation.